Is a Career in Massage Therapy Your Path? Take the Free Quiz

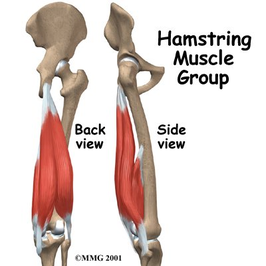

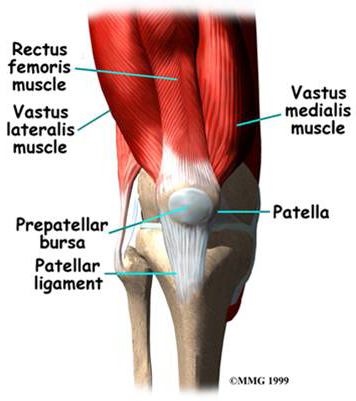

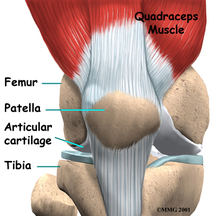

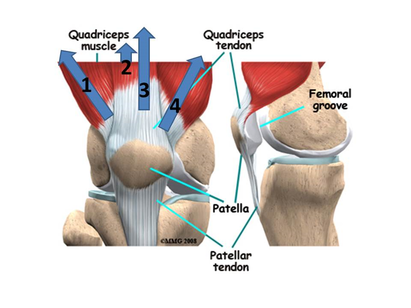

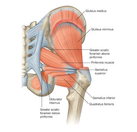

Dr. Dan Rovin's "Danatomy": An Exploration Of The Twenty-Five Muscles Of The Thigh (Part 3)12/22/2017 This Week: The Hamstrings and Quadriceps Femoris, The Group of Three and the Group of Four Dr. Dan Rovin, DC is a senior faculty member at The Healing Arts Center in St. Louis, Missouri and at Southwest Illinois College in Belleville, Illinois. He teaches anatomy and physiology in the massage therapy program at HAC. He has helped train more licensed massage therapists in the region than probably anyone. "Dr. Dan" , as his students call him, is known for breaking down the hard science of anatomy and physiology into easy to understand, often humorous presentations to make this essential science memorable. The English-speaking world calls them the "hamstrings". I refer to them as Biceps Femoris and the Semi Sisters. They work against the muscle group most commonly known as the quadriceps. I teach them as Rectus Femoris and the Vastus Brothers. Together they are the seven muscles that are most responsible for the movements of the knee. More importantly (since we stand, walk, run, and jump), they are the seven muscles most responsible for fixating the knee and preventing falling due to knee instability. Let’s break them down. Hamstrings (Group of Three) The term hamstrings originated in Great Britain. It was not originally an anatomical term taught in medical schools. It was a reference to the sinewy parts of the animal carcasses displayed in butcher shop windows. The tendons behind the knee joint, in combination with the muscles that run to the ankle end of the hoof (hock to fetlock) are very dense on the hind legs of quadrupedal animals. Refrigeration wasn’t available so butchers would hang meat to age and dry upon hooks by the tendons of the back of the knee joint. The hollow of the back of the knee was known as “ham” and the tendons were often referred to as “strings”. Thus, hamstrings became the common word for this set of muscles and through comparative anatomy these muscles on humans became known by the same name. There are three hamstring muscles all working together to flex the knee. Biceps femoris, named for its two heads, is the lateral muscle of the three. Its long head originates with the semimembranosus and semitendinosus from the ischial tuberosity. It joins up with the short head approximately half way down the thigh and inserts into the superior aspect of the head of the fibula. Interestingly, it has a tendency to insert into the outer margin of the lateral tibial condyle as well as the lateral collateral ligament that connects the femur to the fibula. The short head rises from the lower half of the linea aspera and merges with the long head. Though biceps femoris is homologous to the biceps brachii, it does not have a propensity to “ball up” when the knee is flexed in the same manner as biceps brachii when the elbow is flexed. Semitendinosus and semimembranosus start together on the ischial tuberosity just medial to the origin of biceps femoris. At their origin the semitendinosus tendon is very short and almost immediately gives way to contractile muscle tissue. Semimembranosus, on the other hand, has a long, flat, membranous tendon that runs almost half the length of the muscle then tapers to a typical tendon before giving way to contractile fibers. On illustrations where both muscles are drawn together, the fleshy half of semitendinosus covers the flat tendinous portion of semimembranosus. In cadaveric study, separating the semitendinosus from the semimembranosus reveals that the contours of semitendinosus form fit to the deeper semimembranosus. The distal half of these muscles tells a different story. Semitendinosus becomes completely tendinous adjacent to the level that the short head of biceps femoris originates. It then crosses the knee joint and inserts with the sartorius and gracilis tendons to form the pes anserinus (goosefoot) tendon. As discussed in previous blogs, this tendon inserts into the anteriomedial aspect of the proximal tibia and allows the three muscles to work as a unit that stabilizes the medial knee by supporting the medial collateral ligament in a similar fashion to the iliotibial tract stabilizing the lateral knee. The distal semitendinosus tendon is long and narrow and runs over the fleshy, lower half of the semimembranosus. This portion of semimembranosus is relatively unobstructed by the semitendinosus and is visible and palpable through the skin. The semimembranosus insertion is posterior to that of semitendinosus. It inserts on the medial tibial condyle opposite of biceps femoris. Like biceps femoris, it usually joins with ligament, specifically, the posterior joint capsule of the knee and also typically attaches to the back edge of the medial meniscus. Hamstring muscles are responsible for flexing the knee but they are also the greatest synergists assisting gluteus maximus in hip extension. When the knee is flexed biceps femoris laterally rotates the knee yet when the knee is extended it helps laterally rotate the hip. Semitendinosus and semimembranosus medially rotate the flexed knee and assist medial rotation of the hip when the knee is in extension. Popliteus, gastrocnemius, plantaris, sartorius, and gracilis work with the hamstrings to flex the knee. Quadriceps Femoris (Group of Four) There are four quadriceps muscles working together to extend the knee. The term “quadriceps” is a bit misleading. It translates from Latin to English as four (quad) heads (ceps) implying that they are a single muscle with four heads. This is not the case. They are four separate muscles that converge onto the patella. From that point on they continue as a single, solitary unit called the patellar ligament. Many refer to this structure as the patellar tendon, which it is, but since it connects from the patella to the tibial tuberosity (bone to bone) it should be described as a ligament. This group is homologous to the triceps brachii but where triceps has synergists of extension in anconeus, supinator, and the forearm extensors, quadriceps has none. You read that correctly. Quadriceps have no synergists! They are the only muscles that can extend the knee. That means, by default, the quadriceps are the only muscles that prevent the knee from flexing, or buckling, due to gravity or any other force trying to bend the knee. As such, the quadriceps work harder then any other group of muscle when walking. When comparing the knee to the hip or the ankle, the knee is least stable. From the anatomic position the knee can only flex and extend. Once flexed, the knee can be rotated medially or laterally. When walking the knee bends and straightens. The quadriceps easily straighten the knee as the hip is flexed and the ankle is dorsiflexed and slightly inverted. Once the heel strikes the ground muscles of the lower extremity are activated to extend the hip and plantarflex the ankle. The knee flexes during this phase but not due to hamstring contraction. Knee flexion occurs as the result of quadricep contraction eccentrically. Quadriceps, essentially, prevent excessive knee bending until “push off” of the toes and the initial phase of gait starts anew and quadriceps contract concentrically to straighten the knee again. Confused? Basically, when standing, walking, running, or jumping, the quadriceps are working. They are either shortening, concentrically, to extend the knee, or they are lengthening, eccentrically, to keep the knee from flexing and preventing falls. Without the quadriceps your knee will buckle under the weight of your upper body and you will fall down. As such, the quadriceps are the largest group of muscle in the thigh comprising of nearly 50% of the area between the hip and knee. Of the four muscles, vastus lateralis is the largest. It originates underneath the anterior aspect of the greater trochanter of the femur and then spirals around the lateral side of the femur posteriorly where it runs the length of the lateral lip of the linea aspera ending just above the lateral supracondylar ridge of the femur. Vastus medialis originates along the medial lip of the linea aspera ending above the medial supracondylar ridge of the femur. Vastus intermedius, sometimes called the “hidden quadricep”, lies deep to rectus femoris and is only visible on illustrations when rectus femoris has been cut away. It originates from approximately two-thirds of the anteriolateral diaphysis of the femur. The three vastus muscles insert into the base of the patella and continue with rectus femoris as the deeper portion of the patellar ligament to the tibial tuberosity. Rectus femoris is the only quadricep muscle with the ability to flex the hip. It originates on the anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS) and the superior rim of the acetabulum. It travels superficial to vastus intermedius and runs through the base of the patella and becomes the superficial portion of the patellar ligament. Hamstrings vs. Quadriceps

The rectus femoris (superficial most of the four parts) is the only quadriceps muscle that doesn’t attach to the femur. The short head of biceps femoris is the only hamstring portion that cannot extend the hip. Rectus femoris is the only quadriceps muscle that can flex the hip. Biceps Femoris and the Semi Sisters. Rectus Femoris and the Vastus Brothers.

|

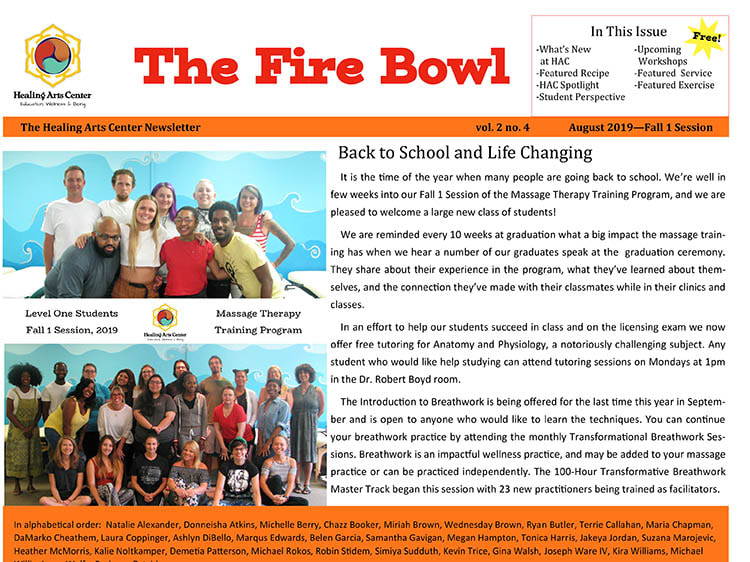

Healing Arts Center News

Keep up with what's happening at the Healing Arts Center.

Follow us on Social Media:Read the Fire Bowl School Newsletter:

Categories

All

|

*The Healing Arts Center is proudly accredited by the Accrediting Commission of Career Schools and Colleges (ACCSC) for the 600-hour massage therapy training certificate only. ACCSC does not accredit individual Master Track courses or CEU offerings separately for this or any institution.

Follow Us Online:

© Copyright, The Center For the Healing Arts, LLC, 2020